LAHORE:

The ageless city of Lahore is known for its liveliness and festivity, and it is an acknowledged fact that Lahoris know how to celebrate an occasion, and celebrate it well. The occasion which Lahore is perhaps most famous for is Basant — the kite festival. The banning of Basant in the city pushed veteran kite-makers into a tizzy. A Lahore-based filmmaker, who has grown up participating in the festival, decided to relay the plight of these kite-making artistes through a film.

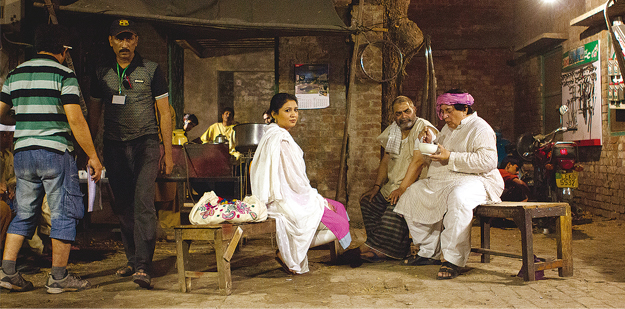

The film, Hun Ki Tera Zor Ni Gudiye (titled Kites Grounded in English) tells the account of a kite-maker whose sole method of earning was by producing colourful, glitzy kites. The story is centred around the life of old Chacha Kareem (played by veteran actor Irfan Khoosat) who, after being rendered jobless following the passing of the Punjab Prohibition of Kite Flying (amendment) Bill in 2009, is gradually losing his passion for making kites.

The storyline is set in the year 2009; the year the ban on kite-flying was first imposed in Lahore. Director Ali Murtaza has long been fascinated by kites, and had participated in Basant every year along with his family. He also knows many kite-makers because of his enthusiasm for kite-flying. He therefore knows the stories of many such kite-makers, who suffered crippling financial losses due to the crackdown.

“The film is not exactly about Basant, the festival serves only as the backdrop of the film. Its plot is based on the life of a kite-maker whose work suffered due to the festival being banned,” says Murtaza. The script is co-written by Murtaza and his wife Seema Hameed, who is the film’s producer. The entire script is in Punjabi, while the film has been shot in old Lahore, a city where kite-flying holds much importance.

The festival of Basant, which has both a rich past and immense cultural value, was defined by Sufi poet Amir Khusro as “a form of internal awakening”. To the people of Lahore, it represents a lot more than just a fleeting recreational activity, or a means of earning ones livelihood. “It [kite-making] is something these people have been doing their whole lives and suddenly, in the twilight of their age, they are subjected to unforeseen circumstances. The story is about a certain kite-maker who has to stop making kites and in the process, realises how much he loved doing so,” describes Murtaza.

The film has been in the making for about two years and its first-look trailer has been released on the internet. Hun Ki Tera Zor Ni Gudiye will be sent to a number of film festivals, including the Berlin Film Festival, before being released in Pakistan in the spring of 2014.

Murtaza spent a lot of time picking out the film’s cast. “Traditionally, casting is a neglected part of film-making in Pakistan. We spent a good three months finding a suitable actor for each character. Irfan Khoosat was in fact the seventh or eighth person we screen-tested for the role,” says Ali, who had first cast Amanullah for the role of Chacha Kareen, but had to recast the part following schedule conflicts. Actor Tasneem Kausar plays Khoosat’s wife, Shakeela, while Abid Kashmiri plays Saleem, a friend of Chacha Kareem.

“Khoosat fitted perfectly because the character of Chacha Kareem is coy, and says very little, most of the time he just listens. He came out really nice in the role.”

Hameed said the urbanisation of Lahore led to the festival being marginalised, and that the aftermath of the government’s decision to ban Basant could only be studied through the eyes of a kite-maker. “We all partook in kite-flying; we were all very much a part of the kite-flying tradition. Everyone I would speak to, whether friends or family, talked about was how these skilled kite-makers had to give up their craft,” says Hameed.

Hun Ki Tera Zor Ni Gudiye has been filmed at Hameed’s family house in old Lahore. When shooting the film, the film-makers used mainly authentic locations and used only a few sets. While writing the script, Hameed said the team had made a unanimous decision that the language should remain Punjabi — something that the people of Lahore will connect to.

Both Hameed and Murtaza were not used to writing in Punjabi. “Punjabi is definitely not my best language, so we got another person on board who was experienced in this dialect, which is also often used in Lollywood script. He helped us tweak the rough edges of the script,” explained Hameed.

The duo is in talks with several local distribution companies and is aiming for a nationwide release. Murtaza says he has already started working on scripts for future projects. He is also certain that the film will be able to portray the disappearing local culture of Lahore in an authentic manner, thus preserving it on film for future generations.

0 comments:

Post a Comment