You don’t formulate movies (like Barfi!) targeting its box-office potential or its commercial prospects. You create such films for its passion of cinema.”

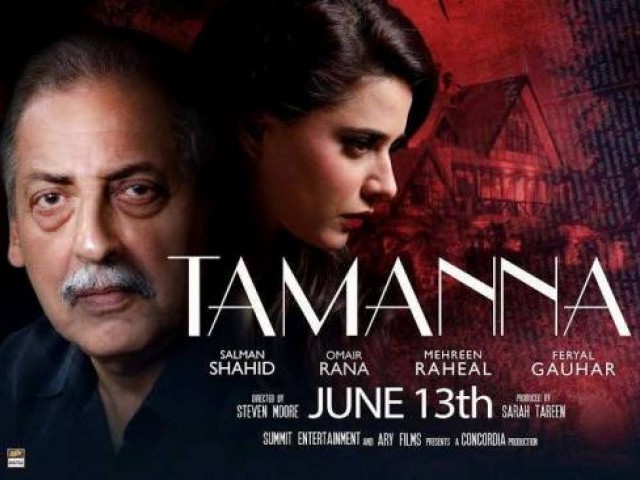

This statement applies to Tamanna as well; which takes several brave strides. It fulfils what it sets out to do and keeps you hooked and guessing all the while.

Based on a well-known Anthony Shaffer play, Sleuth,

the film incorporates elements of dark humour, melodrama, crime,

passion and revenge. This is the fourth adaption of the play on screen,

the first one starring Lawrence Olivier and Michael Caine in 1972,

followed by a remake starring Michael Caine and Jude Law in 2007 and a

made-for-TV West Bengali adaptation.

The

film’s hero is Rizwan Ahmed (Omair Rana), a struggling actor who meets

Mian Tariq Ali (Salman Shahid), a relic of the once-thriving film

industry. The struggling actor, Rizwan, is there to convince Ali to

divorce his wife, played by Mehreen Raheal. A contest of male dominance

between the two men ensues; starting quite reasonably, playfully even,

but eventually turning angry and violent.

Director

Steven Moore has made a mature and evenly paced film, detailed with

layers. The film keeps you interested, attentive and anxious to learn

about what will unfold. While most thrillers only work well if someone

gets caught, here, the story sails through even after you have figured

it all out. I especially enjoyed the scene with the police character,

Faisal Khan; the director made clever use of a load-shedding blackout to

conceal the policeman’s identity and build the anticipation. Also, the

viewer needs to savour Salman Shahid and Omair Rana’s brilliant

performances; one of the strengths of the movie.

Another

important aspect of the film is the stunning cinematography,

complimented by the film’s original background score and songs by local

artists.

The

second half of the film relaxes, where it could be tauter. One grouse

would be that the sub-plots in the story are likely to test your

patience at some points, as the narrative deviates from the pure

treatment, with a lot of twists and turns. However, thankfully, ‘Tamanna’

doesn’t come unhinged. The first rate performances, especially of

Salman Shahid, under Moore’s direction, help steer it to shore.

What does ‘Tamanna’ mean for new Pakistani cinema?

Content

is king in movies, where a new age of realism and portrayal of reality

onscreen has become a common film-making practice, as opposed to showing

a larger than life drama. The set formula used earlier, of a big star

cast, exotic locations and song and dance, is at risk of falling flat

without a solid script and concept. The internet generation is becoming

more aware of world cinema and content quality.

In

terms of cinema, one must distinguish between ‘popular’ and

‘important’. Popular, or mainstream, cinema means remaining within the

expectation of the audience and the dominant ideology of society from

which it arises. Whereas ‘important’ refers to cinema with ideas that

are not yet fully realised or discussed, or are generally

under-represented by the mainstream. In the conventional sense, these

films were considered ‘Art Cinema’ or ‘Parallel Cinema’. This means that

these films are intelligent and they are meant for a niche audience

(read: poor box office).

This

no longer applies, as we see how Indian commercial cinema (in spite of

mainstream Bollywood) has taken a different route of late, entertaining

its viewers with the blend of auteur and new age cinematic realism.

This is evident from the selection of ‘Barfi’ for an Oscar consideration or the official selection of ‘Gangs of Wasseypur’

at Cannes. With directors, such as Anurag Kashyap, Madhur Bhandrakar,

Dibakar Banerjee, Vishal Bhadwaraj, Imtiaz Ali, Nagesh Kuknoor, Santosh

Sivan and Srijit Mukherjee amongst others, and their individualistic

approaches, it is clear that Indian cinema now takes the art more

seriously.

With

all the talk of the revival of Pakistani cinema, or a new age of film

emerging, are we going straight to this situation of having both the

commercial and art cinema, not wasting time catching up like the Indian

cinema did over 20 or 30 years? Time will tell. But Tamanna, with its postmodern stance towards style, is certainly a step in the right direction.

0 comments:

Post a Comment